by Kati Miale | Jul 30, 2012 | News

Former Olympian and professional football player Howard Dell tries to stay cool in the hot sun while talking to spectators at the Transplant Games of America at Grand Valley State University Monday.

ALLENDALE, MI — As Howard Dell took to the track Monday, ready to compete in the, his mind turned to thoughts of what might have been.

Stepping onto the new bright blue track surface brought fond thoughts of Grand Valley State.

Yet he remembers it as a college, not a university.

“Strangely enough, when I was high school, this was Grand Valley State College and they recruited me for basketball,” Dell said. “I still have my recruiting letter from 1981.”

Things have changed in 30 years.

Grand Valley grew into a university in 1987 and Dell’s life has been filled with Olympic competition, professional football, athletics training and even acting.

It was more than he ever planned for.

What he hadn’t planned for was being diagnosed with the rare liver disease PSC (Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis). Then, upon further testing, he was diagnosed with Wilson’s disease, which is caused by too much copper in the liver.

All of a sudden, time was something Dell didn’t have much of.

The attention he was used to getting from athletics and film turned to medical diagnosis and treatments.

“I had the same disease as (former Chicago Bears running back) Walter Payton,” Dell said. “And I’m the only person to ever have PSC and Wilson’s disease.”

Albeit odd that having more things wrong with him may have helped save his life, his double diagnosis got him fast-tracked for a transplant, but barely in time, he said.

Now, just two and a half years out from his successful transplant, Dell is still weighing all his choices on how to continue with his life.

“I’m still deciding what I want to do,” Dell said. “I’ll always want to train the athletes but I’m not sure if I’ll go back and do the whole film and television thing yet.”

In the interim, competing in transplant games has worked well for Dell.

Fresh off winning four golds in the Canadian Transplant Games last weekend in Calgary, Dell is working through a long list of events in these games, his fifth since his transplant.

As if competing in the 100 and 200 meter races, discuss, and the softball throw weren’t challenging enough, Dell is struggling with other things this week — his emotions.

“It feels somewhat unfair, I almost feel bad,” Dell says, referencing his experiences as a professional athlete, now competing against other recipients and donors as well.

Competing in doubles bowling Sunday was a great equalizer, though, Dell said.

“I have trouble getting two pins, let alone all of them,” he said.

by

by

by Kati Miale | Dec 7, 2009 | News

Secret weapon

BY STEVE KILGALLON

A Last updated 05:00 12/07/2009

Photo: Phil Doyle

Ray Columbus says the EECP treatment Will Hinchcliff offers gave his wife back her smile after she suffered facial injuries in a car crash.

Two former athletes are pushing a new treatment which they claim will help numerous Kiwis and save the healthcare system $100m a year.

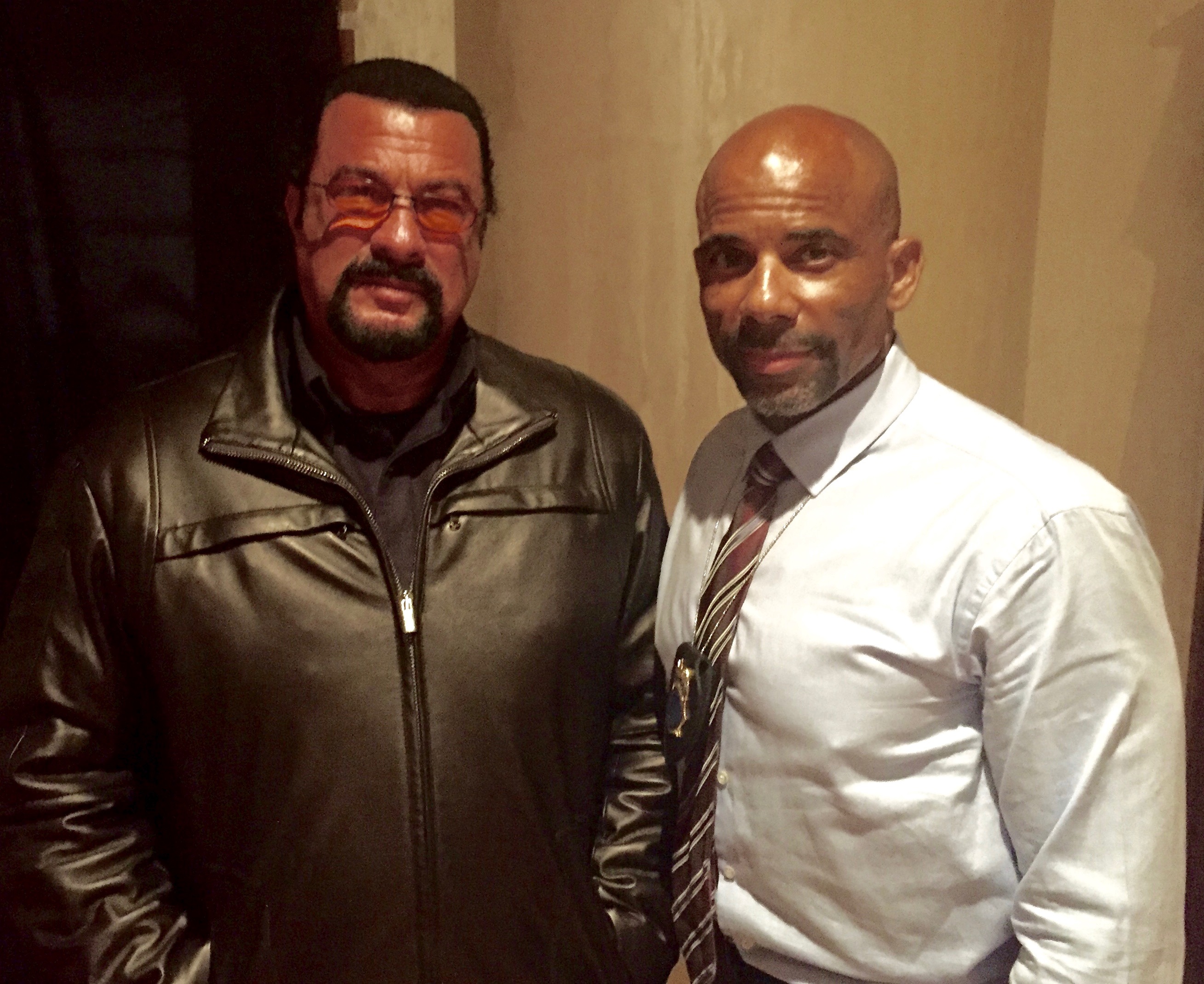

Howard Dell and Will Hinchcliff have both been in their national bobsled teams and both played American football in the NFL. One has a former prime minister for an uncle and served a drugs ban (Hinchcliff), the other was a regular on the Young and the Restless and coaches elite basketballers.

Together, they own a company named Primary Heart Care. Five rooms of an old Auckland villa contain the healthcare system they claim to be the answer to heart disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, Parkinson’s, diabetes, high cholesterol and, yes, erectile dysfunction. A former pop singer says it has even restored his high notes.

And they have the perfect pitch: “We can save the government and the healthcare system $100m a year. If you’re a politician, we’re going to save your constituents, get them back to work, help the economy and help you get re-elected.” (That’s Dell, by the way).

But while they have had a personal audience with John Key, the medical establishment doesn’t, yet, seem to think much of Howard Dell, Will Hinchcliff, or of Enhanced External Counter Pulsation therapy.

Inside theA old villa, and in the interests of research, I lie down on a chest-high bed while Hinchcliff attaches electrodes to my chest and straps blood pressure cuffs around my ankles, thighs and buttocks. This is EECP. In essence, the cuffs inflate, tighten, and push your blood back from your legs towards your vital organs. The clever bit, they say, is that it responds to your heartbeat, creating a reverse blood flow wave. The resulting increase in blood circulation, they claim, has huge restorative effects on the body that are particularly suited for heart patients and elite athletes: their two target markets.

Hinchcliff has absorbed all the science, and as he tinkers with the machine, keeps up a steady patter, telling me how EECP was first conceived in America in the 1960s, refined in China and has now spread to the UK and India.

“With this you can reverse almost every degenerative disease that’s circulation-related,” he says, testing my blood pressure and heart rate before the machine thumps into life. “We can improve your arteries, we can improve your nitric oxide… it’s a massive detox for liver, kidneys and colon… you get better blood flow to your brain, eyes, vital organs. EECP meets the gold standard: the outcome is, you won’t suffer a heart attack or a stroke. All the surgeries [on heart patients] don’t prevent you having another heart attack or a stroke.”

Hinchcliff says the increase in bloodflow from every one-hour treatment has a similar impact to running 35km, while reducing heart rate and blood pressure.

When I jump off the bed, I can’t say I feel very different. The next day, perhaps, there’s a slight feeling of wellbeing: similar to the after-effects of a good deep-tissue sports massage.

Not that Hinchcliff needs my endorsement. The bed already has an almost-improbable list of celebrity backers, from boxing legend Muhammad Ali to basketballer Shaquille O’Neal, and Hinchcliff wants to position EECP as the next elite sports “edge” by offering free treatments to leading athletes.

Darkly, he hints some established sports medical professionals aren’t in favour, but, despite that, he has already signed up Martin Crowe, Grant Fox, boxer Shane Cameron and ultra-runner Lisa Tamati, who used the beds as often as possible in preparing for this month’s 280km ultramarathon across Death Valley and describes them to me as her “magic ingredient”.

Hinchcliff says the reason EECP hasn’t become mainstream sports science is purely a case of the well-informed keeping secrets. “You don’t want to tell your competitors you have got the magic bullet,” he smiles.

And as for celebrity name-dropping? Well, he’s got Ray Columbus. You know, Ray Columbus and the Invaders of “She’s a Mod”? Sure enough, as I interview Hinchcliff, Columbus appears in the office, wearing a red leather jacket, a neat quiff and looking substantially younger than his 67 years. He embarks on an extensive tale of how he came to meet Hinchcliff and then of how Hinchcliff treated Columbus’ wife Linda, who has seven titanium plates inserted in her face after a 1992 car accident. She struggled to smile and when barometric pressure changed, suffered severe pain. Yet after 10 sessions, Columbus says, she was pain-free and after 13, regrowing arteries restored her smile. “It was a miracle; it was unbelievable,” he declares.

Columbus himself was treated for vascular disease, which he says is completely banished, but also suffered a stroke when he became so reliant on EECP that he stopped taking medication. That, he says, taught him that it’s a “complementary” treatment. Unperturbed, he adds that the treatment also helped restore the top-end singing range lost in his 40s by surgery on pre-cancerous nodules.

Columbus features prominently on Hinchcliff’s marketing leaflet. Keith Emirali doesn’t, but he’s an equally vital part of the promotional push. Hinchcliff says he met the 86-year-old World War II veteran when Emirali was undergoing dialysis and promised him better health. Emirali emerges from a treatment room to tell me: “Personally, I have cut my blood pressure medication in half. My doctor couldn’t believe how much my blood pressure had come down.” He’s a test case for EECP; Hinchcliff later waves a letter from Emirali’s GP in front of me, and has enlisted the RSA to plead his case with the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs that they should fund free treatments for veterans.

After an audience with prime minister Key last month, the result of extensive lobbying, Hinchcliff pitched for a 100-patient pilot involving heart patients on a surgery waiting list. He’s now waiting to see if that translates into any official backing. “I am hoping the law of gravity now takes over and it trickles down to the right people,” he says.

A few weeks later, Hinchcliff calls to tell me a government committee, which evaluates new medical treatments, will consider EECP’s merits on August 9. He explains the process, which appears remarkably tortuous even by bureaucratic standards, but it seems to have renewed his confidence.

I hope it has cheered Dell up. On the phone from Newport Beach, California, a few weeks after my initial conversation with Hinchcliff, his business partner had been less optimistic, railing against the Kiwi immigration department, our medical establishment and our insurance system.

Even the fact that the debonair, well-spoken Canadian-born soap actor is in the Californian sunshine not the Auckland drizzle is irritating him. He’s been out of the country for three months, part of a two-year campaign to persuade immigration to replace his visitors’ visa with a work permit.

“I’ve had some trouble with immigration. I just don’t know how they let overweight, obese people come into the country and they won’t allow me, with $750,000 invested into this country, to come in,” he says mournfully.

Both Dell and Hinchcliff hint they will take EECP to Australia if New Zealand doesn’t embrace the treatment, but Dell insists he’s still enthusiastic about a breakthrough here. But he also says: “New Zealand is a great opportunity. But it is like introducing penicillin to these islands. We’re bringing in something new and inexpensive that will save lives, and the Kiwis are like `Oh, I dunno’. But it’s hard for cardiologists to swallow. If you’re my patient, and I’m your cardiologist, our relationship might be worth $1m to me over the years once you consider a few stents, the drugs, the surgery, consultation hours. EECP costs $13,000 to $14,000 and you’re cured. $1m versus $14,000. What would you rather have?”

After talking about potential multi-million dollar savings in lost work time, insurance payments, expensive surgeries, surgeon’s salaries and hospital space, Dell goes on to say that most of the New Zealand medical establishment would, if they were in the US, “be in jail” for conflicts of interest such as sitting on the boards of drug companies and medical insurers. He suspects they actively dissuade patients from trying EECP. “But it’s already in the best hospitals in the world. These New Zealand doctors think they are smarter… they could at least have the decency to listen, to learn.”

Primary Heart Care do have a medical advisor, heart specialist Dr Gerald Lewis, who doesn’t reply to an emailed request for an interview, although Hinchcliff is vague on how often he visits the office. Hinchcliff himself is doing everything on the two occasions I visit, and says he has six months’ training as a qualified EECP technician. It appears that you don’t need a doctor’s referral for treatment, but he screens patients and the machines switch off automatically if your blood pressure or heartrate is dangerously high.

It wasA Hinchcliff’s idea to introduce EECP to these shores. Nephew of former prime minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer and son of AUT philosophy professor John Hinchcliff, Willie Hinchcliff was a New Zealand long jump champion who wore the black singlet at the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland, but was then busted for steroid use and banned for two years.

Hinchcliff’s athletic CV, however, was far from complete. He made the New Zealand bobsled team for a world championships in Canada, and there he met Dell, in the Canadian sled, and the American Olympic medal-winning sprinters Quincy Watts and Sam Grady, who were in the US sled. Dell secured Hinchcliff a season with a Canadian football team (the 1991 team picture of the Toronto Argonauts, including both men, hangs on Hinchcliff’s office wall). The other two got him something even better: a deal with their agent, Steve Feldman (the real-life model for the film Jerry Maguire). And Feldman got Hinchcliff a trial with the NFL’s LA Raiders.

Although he knew nothing about gridiron, he could run very fast, and that was enough. So for the next 10 years, he was a near-unique Kiwi presence in professional football, bobbing around the Canadian and American leagues, with an interlude at England’s London Monarchs.

Dell and Hinchcliff met again in 2001. Hinchcliff had retired, moved back to Auckland, and found little to amuse himself with. Back in California on holiday, he was in the fast lane of the 405 freeway when a car overtook on the inside. He glanced up, and saw Dell. “I chased him down the freeway and pulled up beside him, and he thought I was a lunatic. That’s how we reconnected.”

Dell, whose equally varied CV included college basketball, competing in the decathlon, playing gridiron for Cincinnati, Toronto and Winnipeg, and TV and film acting, was now working for a company which marketed EECP in the US and invited Hinchcliff to come back for some treatment.

Dell had discovered EECP years earlier when he was advising a group of world-class athletes, including sprinters Maurice Greene, Ato Boldon, John Drummond and Watts, when one said he was planning to try out EECP. Dell says he acted as the guinea pig and loved it. Hinchcliff had hit on it during his gridiron career, and credits it with adding five injury-free years to his career. Together, they saw an opportunity.

Given they have exclusive New Zealand rights to the concept, if they did get government support, they stand to make a hell of a lot of money. “By saving the government money, the business has an opportunity to grow profitably,” says Hinchcliff. “There is an opportunity to make money but the reality is, the equipment costs a lot of money.”

He talks about his gridiron career, where his first contract was worth seven figures and the sign-on bonus paid for a house, and says: “I won the lottery, I was blessed”.

“It’s given me the capital to invest in business. I could go buy three Ferraris right now, but I am creating a lifestyle of giving… [which gives] a lot of satisfaction. I can’t do wrong by doing right.”

Then he laughs. “And if they still don’t like that, I’ll move to Australia.”

– Sunday Star Times

by

by